Making a Difference with Corporate Sustainability

At All Heart NZ, we partner with businesses to create sustainable solutions for unwanted corporate items. By repurposing and redirecting resources, we reduce waste, support

The word is thrown around a lot. But with many different definitions and uses, it is no surprise that there is still some confusion around it. So what actually is sustainability?

SUSTAINABILITY

The term sustainability became common in the 1970s as the result of the growth of the environmental movement and as of international agencies such as the UN adopting it.

The basic principles behind the term are holism and longevity.

Holism means that when we think about making something sustainable – like a business or an entire economic system, we must consider its relationships with its broader environment; longevity means we need to manage it in such a way that it continues to work for a very long time.

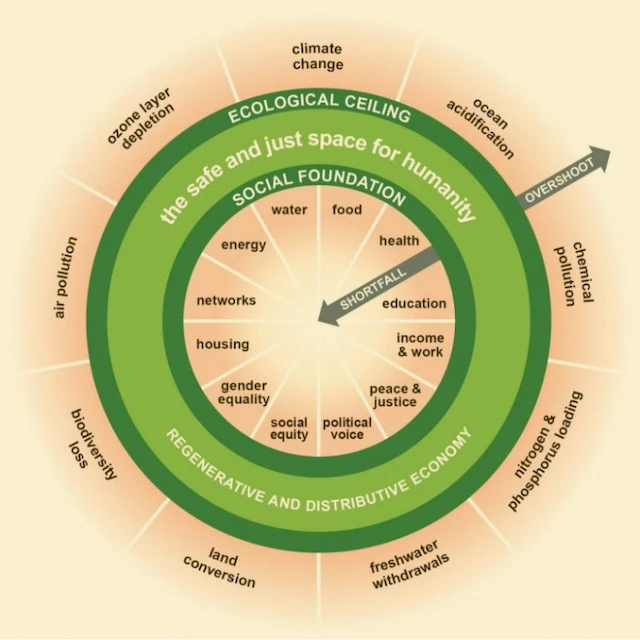

For example, analysing the sustainability of our current human needs (economic, social, cultural, etc.) means considering them within the broader environment in which they exist, that is, our planet. It also means paying close attention to the ability of this environment to satisfy these needs for people existing now and for future generations.

Most commonly, the word sustainability is used to refer to the balance between the rate of human consumption of resources with the planet’s carrying capacity: it’s ability to regenerate these resources while satisfying our basic needs.

SUSTAINABILITY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

This brings us to a very important issue: the fact that the idea of basic needs differs depending on who you ask, where in the world you are, the individual’s culture and many other factors.

For example, what individuals in rural areas of the developing world consider to be their basic needs differs greatly from what individuals in industrialised urban centres in the developed world consider to be theirs/ours.

This gives rise to what is known as the Brown Agenda and the Green Agenda of sustainable development. The Brown Agenda encompasses issues usually – but not always* – found in the developing world, such as access to clean water and appropriate housing and sanitation which affect people’s most basic needs. The Green Agenda relates to issues found in wealthier countries – like Aotearoa New Zealand, such as overconsumption and resource depletion, which affect socio-ecological systems and future generations.

Because environmental damage is often a cause and a consequence of poverty, solving many of the problems in the Green Agenda depends on solving – at least to an extent – the problems of the Brown Agenda. Thus, poorer cities and countries tend to focus on the more pressing needs of the Brown agenda before they can move on to tackling Green Agenda problems, while wealthier ones have historically been able to focus on them sooner. In either case, the idea that the unequal rates of consumption – the different understandings of basic needs – that exist between the developing and the developed world and/or the rich and the poor must be central to our sustainability efforts.

This is where Sustainable Development comes in. It is often defined as ‘development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland, 1987). While scholars and practitioners have criticised it for being too elusive and broad, the crucial points it makes is that sustainable development requires a balance between the economic, social and environmental spheres of human influence – the three pillars of sustainability – and long-term strategic thinking and commitment to the future.

THE THREE PILLARS OF SUSTAINABILITY

Modern definitions of sustainability recognise that human basic needs encompass the economic, social and environmental dimensions of human life – the ‘three pillars’ of sustainability – and strive to achieve a balance between them.

The economic pillar has traditionally been given priority by governments and international organisations. It focuses on the ability of an economy – from a national to a household scale – to continuously deliver returns over an undetermined period. This usually extends beyond the short-term planning that dominates the most corporate activity.

The environmental pillar is what most people think about when they think of sustainability. It encompasses all aspects of the ecosystems that enable society’s activities. As ecosystems are ultimately connected, this pillar requires us to think in very large temporal and spatial scales and consider the impact of our actions on existing and future ecosystems and on the future generations that may not be able to enjoy them. The current climate crisis is a perfect example of the importance of this pillar. It is primarily the result of activities initiated in the industrial revolution, its effects are felt far from where the problems are caused and will continue to do so for years to come.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, we have the privilege of having a rich tradition of successful environmental management available to us as the principle of kaitiakitanga, or guardianship, based on Mātauranga and Tikanga Māori.

The social pillar is the most neglected and least understood dimension of sustainability. This is because it seeks to address some of our most difficult and long-standing social problems such as inequality, discrimination and lack of political inclusion. As such, it includes concepts such as well-being, equity, dignity and democracy, emphasising the need for a sustainable life in the individual, community, societal and human dimensions of life. These are all connected as, for example, dignified employment leads to an individual being able to meet their basic needs, improves their well-being and contributes to the economy.

STRONG VERSUS WEAK SUSTAINABILITY

The traditional prioritisation of the economic pillar over the environmental and social ones often results in policies and trade-offs that harm society and the environment.

One way to manage this is to adopt a strong sustainability approach. Strong sustainability argues that environmental capital (e.g. clean air and water or a liveable climate) cannot be exchanged for human capital (e.g. economic activities). Weak sustainability argues that environmental and human capital are interchangeable.

Strong sustainability maintains that, for example, we cannot assume that the market or technological advancements will ‘figure out’ a way to deal with greenhouse gases or provide food when our soils have been depleted of nutrients beyond repair. It forces us to consider the impacts of our socio-economic decisions more carefully and adopt socio-economic practices more in line with the principles of Circular Economies.

On the other hand, weak sustainability defends the view that destroying our forests and overfishing and polluting our oceans may lead to increased economic benefits that may replace these ecological services for current and future generations. It puts us in danger of underestimating the impacts of human activity on the environment since we do not fully understand how deeply interlinked ecological systems are.

WHY SHOULD I CARE AND WHAT IS IN IT FOR ME IF I DO?

It is obvious that strong sustainability is the clear path to choose – at a business and an individual level. Yet, it’s not always obvious how to choose it, and modern business does not always encourage or allow for it.

Our next blog will dive deeper into why you and your business should care about sustainability and how, contrary to what many corporations think, it is a sure way to help your business thrive.

*It is important to remember that although Aotearoa New Zealand is considered a wealthy country when compared with the rest of the world, there are many areas of our country which still have ‘Brown Agenda’ problems.

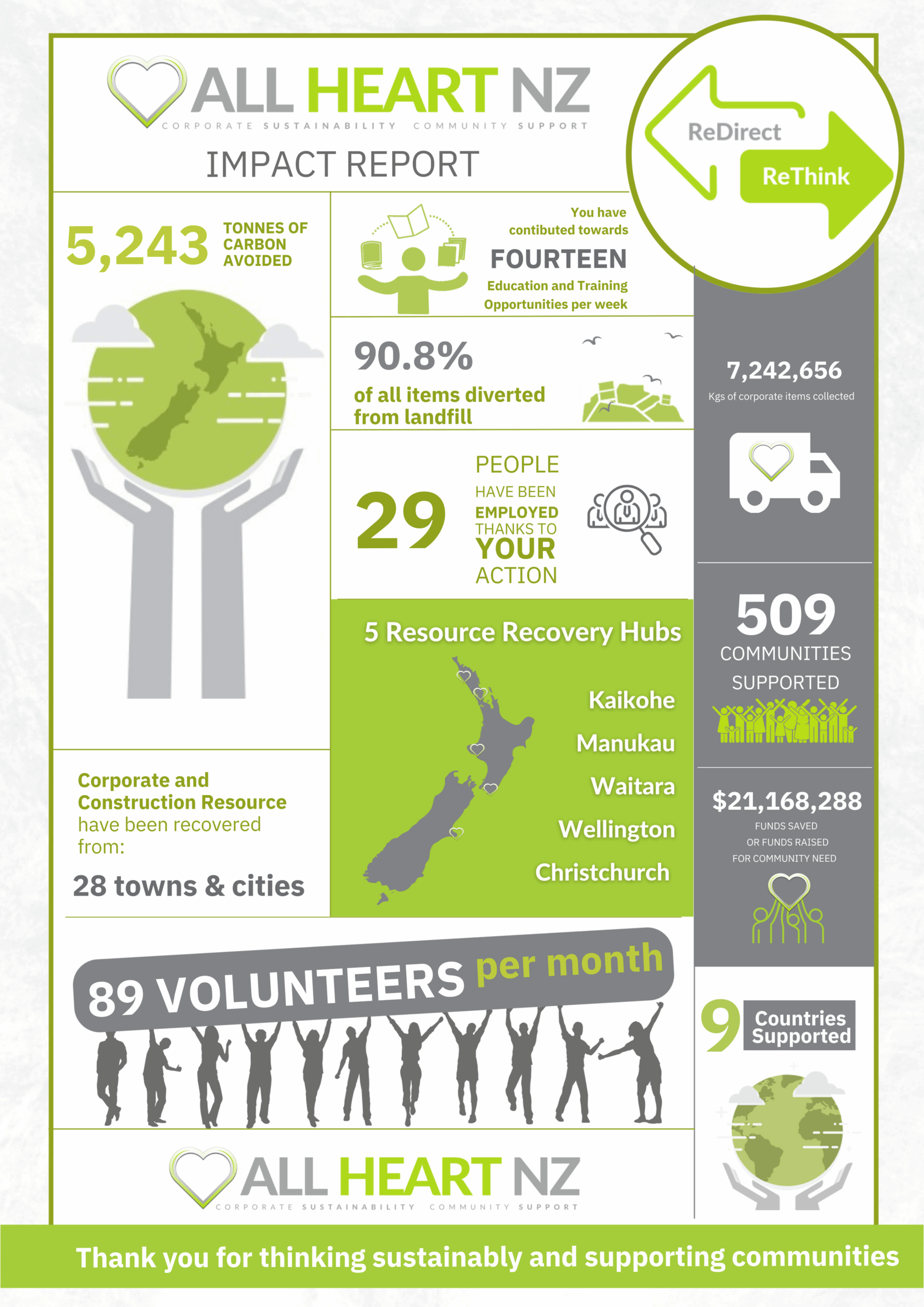

All Heart NZ is a charitable trust. We believe that sustainable business practice can positively affect the lives of people and our planet. We see the value in recovering resources and establishing a circular solution that put people and planet first.

If you are a business who believes in sustainable operations that positively impact people and our planet, check out our services and find out why All Heart NZ truly is a one-stop sustainability solution. We are here to help your business thrive!

If you are someone who is after good quality pre-loved items and wants to make a positive impact in our communities and our environment, then shop for good at one of our All Heart Stores.

FURTHER READING

About – A Good Life For All Within Planetary Boundaries. (n.d.).

Adams, W. M. (2009). Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World. Routledge.

E. Mabee, W., Jean Blair, M., T. Carlson, J., & N. M. DeLoyde, C. (2020). Sustainability. In A. Kobayashi (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition) (pp. 157–163).

Elliott, J. E. (2006). An Introduction to Sustainable Development. Routledge.

Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and Inclusive Development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 433–448.

Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.

Overton, J. (1999). Sustainable Development in the Pacific Islands. In Strategies for Sustainable Development: Experiences from the Pacific (pp. 1–15).

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist

At All Heart NZ, we partner with businesses to create sustainable solutions for unwanted corporate items. By repurposing and redirecting resources, we reduce waste, support

Did you know that thousands of quality items destined for landfill are being redirected to make a difference? 🌟 At All Heart NZ, we partner

Meet Julie, our incredible Business Development Manager at All Heart NZ! She’s the friendly voice behind the calls and inquiries 📞 and the powerhouse driving